- Home

- Rafe Posey

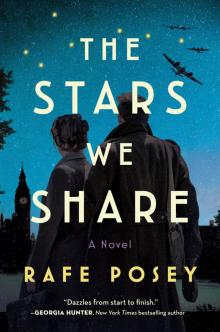

The Stars We Share Page 12

The Stars We Share Read online

Page 12

June carries that letter in her pocket, a simple folded card with someone else’s plain printing utterly unlike Alec’s exuberant scrawl. A few sentences about the Italians taking good care of them, a comment about olive trees in the mountains. Nothing about what’s happened to him that has made it necessary for another man to write his letters for him, except a single throwaway line—banged up my hands rather in the last shaky do. She wrote to Floss in the hopes of learning more, but it’s been weeks now, and she has heard nothing.

It’s possible there are other letters in this confounding handwriting waiting for her somewhere. The post at Anderson has been regular enough, but there are girls whose letters came while they were temporarily elsewhere. Mail forwarded or lost and never seen again. Even Pamela, whose fiancé is still only as far away as India, is subject to the maddening tides of communication. It’s likely enough the same has happened to her, that Alec’s letters are caught in the system somewhere. She gathers from things she’s heard from her mother, or from the Wrens, that the post is equally inconsistent the other direction, but nevertheless she writes to Alec once a month—it’s not often enough, and she feels sick over it, but it feels less bad than more letters compounding the deception. The more often she writes him, the worse she feels, sending half-truths to this man who loves her with all his heart, going through God knows what in Germany.

But sending off these letters is the least she can do. Perhaps there is a middle ground of sorts between the kind of woman she is and the kind of wife she does not want to be. Given what she knows of the German camps he may need more than she knows how to give. Duty means something new now. And so, perhaps, does love.

The roof rustles again, and June tries to relax. Probably it’s Box, hunting. It helps that the mongoose is so good at being a mongoose; it helps her keep the fears at bay. Box has been with them since spring, killing kraits and chasing the larger insects, and one of the other girls swears she saw him hypnotize a cobra. June is reasonably sure this is not strictly true, but it doesn’t matter. Wherever Box wants to go in their compound, he is welcome, although she wishes he would stay close.

So far they have been lucky; except for the kraits that Box tackled, and one scare with a viper, all the Wrens have avoided the snakes. Not that there’s time to think about them—the signals come in fast, and the work of either transcribing or decrypting them is endless and precise. Most of the time it’s Wrens capturing the signals, then sending them around the corner to June or the other codebreaker. The Japanese meteorological codes are beautifully ordered, intricate columns of numbers that June must unravel until they turn to messages.

But often as not June is happy to do the Wrens’ work—they face the same risks, and the lines between who is a Wren and who is not seem sometimes to have collapsed. The night before she had taken Lucy Kent’s shift, because Lucy, who is barely twenty, wanted to go to the Silver Fawn with an officer she’d met the day before. And everyone knows that June will take all the shifts she can—ask Attwell, they say.

Time passes because she forces it to pass, or so it seems. Ceylon is both Shangri-La and Purgatory. When she arrived, there was a skeleton crew of codebreakers and wireless operators; most of the Far East Combined Bureau had gone to Kilindini or Delhi by then. Set up in an old whitewashed building that had once been a school for the sons of landowners, politicians, and prosperous merchants, June and her colleagues had operated more as a way station than a proper outpost for a long while. That had changed last September, when FEBC had come back to Colombo. It’s better now, with the Wrens. Before, it had been so lonely, no matter how deep she had sunk herself in the work. Now, though, it’s more like Scarborough, or even Bletchley Park.

For the most part, June would rather be here, listening to the scratch of her pencils or the static-blurred world beyond Ceylon. If only the weather would cooperate. Monsoon season is mostly past, and in theory it is the best time of year throughout Ceylon. Often there is rain despite the change of seasons, and thunder too, crackling through the headset until her head hurts. But worse than the deafening interference from nearby power lines and the local airfield or the rain is knowing that they may be missing codes—a transposed digit, a dot noted in place of a dash, can mean life or death. There is no margin for error. Even when their shifts change at the wireless, there is an elaborate dance of headset and pencil so someone is always listening, someone is always writing. They cannot pause, ever.

But tonight, beyond the weather, there’s a low whine, like a dog or an old lorry. It’s not one of the usual night sounds, and she’s never heard it before over the headset, either. She stands and goes to the wireless room, where Lucy Kent is now back on duty after her night off. June stands next to her, trying to place the sound, which is now getting louder and more insistent. And then it crystallizes for her—it’s an airplane, too low and too close, and it reminds her of London in the Blitz.

One of the navy men bursts through the door. “Shelter now, ladies! Zeroes incoming!”

Lucy glances out into the night, still listening to the headset. “Can’t,” she says. “Too much message traffic.”

“I’ll take it over,” June says.

“Sorry, miss,” the sailor says to June, his breath coming too fast, “orders are to get civilians to safety!” He hovers behind Lucy. “You too, Kent.”

They all flinch as the plane rumbles overhead, the guttural throb of the engine filling the room. The angry pocking of the guns follows, and the sailor and June crouch low until it passes. Lucy hunches closer to the wireless, her face gone pale. Outside, someone is screaming.

Lucy stands, the headset in her hand, Japanese messages still trickling through the static and out into the room. June reaches for it, but Lucy doesn’t let go. The three of them are still standing like that, viscous black smoke rolling into the room, when the plane passes again. Bullets from its guns lace through the palm leaves and send fragments blasting into the room. One bayonets the sailor in the base of his throat, and he drops, blood welling like spilled milk.

“The shelter!” June shouts. Time is moving wrong, and she can’t shake the sound of the plane. She can barely see through the smoke, just enough to see Lucy still hesitating. And another plane, the engine protesting.

Then the roar of engine vanishes in the shriek of metal twisting into trees and concrete. Lucy drops to her knees, screaming, and in the instant before the plane explodes, June dives to cover her. We should have gone to the shelter, she thinks. Then the sound of the explosion rolls over her, deafening her, and the wall shudders against the blast. Fragments of tree and metal and glass explode around them. The world goes dark.

* * *

• • •

She wakes in the infirmary two days later, dizzy and weak. A scattering of small shrapnel wounds itch as they heal, and her arm is in a sling, a separated shoulder jammed back into place. Her knees, her face, the side of her head . . . everything hurts. Doctors and medical staff hover, check her chart, examine the wounds, vanish again, the tide of them ebbing and flowing according to some schedule June can’t identify.

Another set of days pass, and Wendy comes to visit her, her face drawn. “You saved that girl’s life,” she says without preamble.

June looks down at her counterpane. Lucy is bruised but back at work in the wireless hut, according to one of the medics, but June keeps thinking of how she hadn’t managed to save the sailor. “She was awfully brave, staying with the wireless like that. If it were up to me she’d be in for a promotion.”

Wendy smiles. “Braver than I would have expected. She’ll go far, I should think. But so could you.” She shrugs and pulls a sealed packet from her bag. “In any event, these came for you while you were . . . out.” She pats June’s good shoulder and leaves the packet on her lap.

“Can I ask you something?” June tries to sit up straighter, though the effort sends a thrum of pain through her. They are close eno

ugh that she knows there are Fairchild parents in the Midlands somewhere, but she and Wendy, like almost everyone else in their world of make-believe, have never delved much deeper into each other’s lives.

“Of course,” Wendy says, her face creasing with concern.

“I wondered,” June says, and pauses, unsure how to continue. There is the Act to avoid, and while their covert careers have had a fair amount of overlap, they have diverged quite a lot as well. “I wondered what you tell your people.” She gestures at the packet Wendy has handed her. “Being laid up like this has brought it home, rather, not ever being able to say a word.”

Wendy studies her hands while she considers her answer. “Not the same for me, I suppose,” she says at last. “I don’t have anyone waiting for me like you do, except my parents. Of course, they lost the plot years ago. Told them I was off to the Wrens and bob’s your uncle.”

June nods, pondering Wendy’s response. It makes sense that as a Wren her friend has more options, or at least more cover. A Wren could at least tell her people she is stationed overseas and leave it at that. “Thank you,” she says after a moment. “That helps.” Though it doesn’t, really, not at all.

“You’re quite welcome,” Wendy says. “And, Attwell—good show, the other day. Not a lot of us would have had the wherewithal to pull that off.” And with that she lets herself out.

June turns her attention to the packet. There’s not much there, but the battered card from Alec hits her like a punch in the gut. She has wondered before if they will both make it through the war, but this is the first time, confined to her bed, she has ever wondered if somehow he will survive and she will not. She turns the card over. It’s cheap stock, postmarked from Germany six months earlier, routed through the usual channels. Am safe. Prisoner at Stalag Luft I in Germany. I hope you will write via the Red Cross. Love to everyone. God, it sounds nothing like him at all, and the handwriting is still not his. The math of it doesn’t make sense—when he was still in Italy he had said his hands were banged up, but that was so long ago. What has happened to him, to his hands, that would leave him still unable to write to her?

At least she knows where he is now. Or where he was, six months earlier, which will have to suffice. She pauses over I hope you will write. Likely the systems are failing once again. No matter—this is progress, of a sort. Six months ago, he was alive. She looks in the pouch again, and finds a note from Floss:

I’m sorry to hear that Oswin is in one of the German camps. We hear of unspeakable conditions, and while they are not as savage as the Japanese camps they are hardly fit, some of them, for our men. I do hope he’s well enough, when the war ends, to come home. I’ll keep my ear to the ground, but I shouldn’t hold my breath if I were you. No news is better than bad news, as they say.

More to follow—F.

She puts Floss’s note aside and holds Alec’s card to her chest, and for the first time since she was a very small child, she thinks about praying. But the deity of her childhood seems as unreal as ever, and instead she writes back to Floss, thanking him for his note and hoping he can find out more. And she writes to Alec as well, telling him to hold steady. She doesn’t mention the Zero to either man—Floss likely already knows, and Alec never can.

After another week in the infirmary, the doctors take the stitches out of the back of her head, where a piece of shrapnel had left a cut like the bite of a large bird. When they order her to take ten days of leave, she protests—she has already been out of the codes for more than a fortnight and the business of stopping the Japanese feels more urgent than ever. She takes her convalescence in the hill country, where it’s cool and the trees are full of birds and animals so lush she is half-convinced she’s imagining them. She spends the first day in Kandy, exploring the ancient city and its temples, wondering what Alec would think of them and then shying away from those wholly futile questions. From Kandy she makes her way up to the plantation the officers use as a getaway lodge, complete with golf and dressing for dinner. Local boys shear the tops from coconuts for her, and an old Tamil woman in a dark red sari, gold rings in her nose and ears, brings her tea every morning in a quiet room looking out over the shaded green fields. The food at Anderson is good—there is always strong coffee and fresh fruit, always enough to eat—but here it’s another level up. She has fruit and hoppers at breakfast every day, letting the yolks of the eggs run across the crisp edges of the thin sourdough bread, lacing all of it with a spicy pol sambol. In the evenings, she avoids the dinner crowd and stays in her room, and the old woman brings her coconut shredded into greens and dishes of fish curry laden with coriander sprigs and redolent of tamarind and lime. There are so many fireflies at night that sometimes she struggles to find the stars; the whole dark sky is laced with life.

Too, the days of luxury have filled her with a new kind of guilt—she has felt bad for a while now about the food at Anderson, given the privations her parents, let alone Alec, must be facing. To sit on a verandah and watch thrushes and bulbuls flit through the afternoon light makes her feel like Marie Antoinette, or worse. She has never been anywhere so peaceful as this, surrounded by birdsong, and there is no guidebook or care instructions to tell her how to feel when purple-faced monkeys leap through the trees, their strange barking calls echoing off the lodge. But Alec is in a German prison camp, and the war is still on, and she needs more than ever for this to end.

After the war she’ll have to find her way back into a normal life again, and all of this will be a scar of sorts, hidden quietly beneath her skin as if a companion to the pale V-shaped line beneath her hair. She will never be able to reveal these scars to anyone, least of all Alec.

* * *

• • •

And throughout her recovery, the question of what her future is meant to hold nags at her. There might have been a point at which she could have chosen a path that severed her from Alec and gave her the Wrens or the Foreign Office instead. But now that moment, whenever it was, seems hazy at best. And, in the larger picture, it has become irrelevant. Alec is a captive now, and keeping her promise to him is how she can save him, if there is anything left of him to be saved. Before the POW camps, perhaps she would have found a way to keep following this path of numbers and logic. Perhaps, even in the volcano of heartbreak that would have resulted, they would have been all right. But now it seems unlikely that Alec would heal from such an event. On the contrary, he will probably need her more than ever. A decent woman would honor her commitment to a man like Alec.

1945, Stalag Luft I

At Stalag Luft I, the Baltic Sea is not even a mile distant, and the same grim January wind that curls the snow across the frozen shore slices down through the camp like a bayonet. The camp is L-shaped, with a forest to one side and fields to the other, all of it surrounded with miles of barbed wire and guards who are as ready for the war to end as the men they’re watching. There is not much hope, and never enough food.

The men—Kriegsgefangene to their German captors, but kriegies among themselves—huddle in their barracks, pulling ragged blankets and what’s left of their clothes close for whatever warmth they can offer. But they’ve been wearing the same two uniforms day in and day out since the Red Cross issued them last summer, and what’s left is threadbare and filthy, the ragged seams singed in places from the men’s efforts to burn out lice and fleas. Alec is lucky—Smasher is in the better of the two North compounds, and sometimes the men there have enough running water or fragments of soap that they can perform a sort of rudimentary laundry. In West, where Alec shares his room with eight other officers, the lot of them crowded into three-tiered bunks with shoddy mattresses filled with wood chips, they’re glad just to have indoor lavatories.

Until October, it had not been so bad. The food had been dreadful, but it had been just enough, combined with their weekly Red Cross parcels, to sustain them. A man could live on a bit of bread and margarine to start the day and a handful of potat

oes and cabbage boiled with a small hunk of horsemeat later on. Sometimes there was a dab of marmalade, or a cup of barley soup. But in October, everything had changed. Until the end of last month they had been down to half a parcel each week, and at the same time their German rations had winnowed away to almost nothing—a potato most days, the heel of an old loaf, weak broth with a parsnip or a chunk of beet.

In Campo 78, the men had been glad not to be in a German camp, and now Alec knows they were right. His progression from there to the interrogation camp at Dulag Luft and then north to this barren strip of Pomerania, with its washed-out sky, had felt like a descent into a new kind of horror. In Italy there had been certain comforts their captors had arranged, and while those had not dampened the sting of captivity, they had made a way to mark the time. Some of the same comforts exist here, but they feel rather different. Grimmer. There is a library of sorts, football on some of the grassless yards outside the barracks. There are concerts sometimes, men performing pieces from Peer Gynt or thundering sections of Tchaikovsky, on instruments borrowed from the Germans or built from the leftover slats of broken bed frames. In the autumn, when the weather was less unforgiving, he had found ways to join Smasher for a walk around the fences, the two men talking of the lives they hoped to resume—or start fresh—if the war ever ended. But the heart of winter, and new edicts from the camp’s commandants, had ended that.

At Christmas, an artistic Cornish lad called Fred, one of Alec’s bunkmates, drew up a menu with traces of holly and mistletoe laced around the edges. Alec has no idea what Fred had had to trade to the Germans to get colored pencils, or if they were remnants of the crayons that had once come in Red Cross parcels. But it had made Christmas feel nearly like a celebration, or at least like there might be a reason to celebrate sometime in the future—reading the words plum pudding with white sauce or deviled ham entree took them out of the truth of it, just for a moment. The miserable kriegie bread, underbaked on their rudimentary stoves and often a bit soggy until a man could find a way to toast it, and topped with potted meat and a dribble of Klim, could stand in for a Welsh rarebit if he tried hard enough. And sometimes it was easier to try.

The Stars We Share

The Stars We Share