- Home

- Rafe Posey

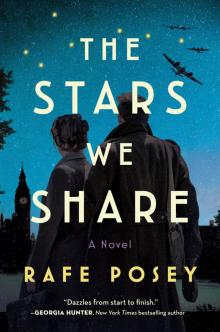

The Stars We Share Page 3

The Stars We Share Read online

Page 3

“I saw the new Aston-Martin just before I came back from London,” Alec says. “The Le Mans.”

“Bloody lovely machine,” Roger says. “Two-seater?”

“Yes,” Alec says. It had sat idling in a street not far from school, and the rumble had got into his bones.

A bevy of sparrows jerks into the air; Noor startles. Roger tightens the reins around one hand and rubs the other along Noor’s mane. “Come down with me tomorrow, if your young lady can spare you, and we’ll see if we can’t get you closer.”

“Brilliant,” Alec says, rattled by your young lady. Is June anyone’s young lady? Could she be? June has always seemed to him to be just her own. He is June’s to his core, but he’s less certain that she is his. It’s an uneasy thought, though an intriguing one, so he concentrates on the cars he’ll see. In his mind, the engines expand into a barrage of sound. He has always loved that thrum and thunder. The idea of speed washes over him again, but this time he imagines himself in the low-swooping seat of an Aston-Martin, roaring along the straightaways in a dusty fever.

Roger leans down and claps him once on the shoulder. “Good lad. I’ll see you at home, yes?”

Alec nods absently. Noor whickers, and then she and Roger are gone, the sound of hooves retreating into the distance.

* * *

• • •

Brooklands is a grand spectacle, a shiny world that smells of petrol and rubber. Roger knows everyone, knows everything, and Alec follows him from car to car while Roger smokes and chats with the drivers. These are men Roger has known for years, and they talk about liters and speeds, about the patches in the concrete track that have left it so rough that cars leave the earth for seconds at a time. It’s hot in the sun, and a line of sweat creeps along Alec’s spine. But being too warm is better than the too-cold of recent winters, which left him raw with longing for India. He blinks the dust out of his eyes and listens to Roger. There are quiet exchanges of pound notes, gibes about bad bets and long shots.

Roger seems closest to a group of men gathered around a brace of Alfa Romeos, bright racing red and green. He pauses to sip from someone’s flask as they drink in memory of a man they call Tiger Tim, recently dead of septicemia after a racetrack injury in Tripoli that spring.

“Heroic,” a man says. He looks at Alec. “Had a glory of a Bentley.”

Roger nods, drinks. “Used to get up to nearly a hundred forty,” he says, shaking his head in admiration. The men murmur.

“Track’s not good for it,” the other man says. “But Tiger Tim, he broke his own record time and again.”

Alec absorbs this quietly. What must it feel like to move so quickly? To roar like lightning across the track and feel the pull of gravity and the car on the steep banking curves?

That afternoon he sits with Roger and his friends and has a pint like the other men. He watches how they move. There are boys at school like that, nearly men, who fill the space around them, and boys who don’t. Alec knows he is somewhere in between; he has just begun to feel the way he occupies his ground. Cricket helps, because everyone knows who he is. His height helps too; he’s nearly as tall as Roger now, and looks older than a few weeks from fourteen.

“Tomorrow afternoon there’s women racing the course,” one of the men says. “Reckon there might be some good motors, though.”

Another man leans off to the side and spits. “No place for ladies here,” he says. “Although . . . A woman who wants to race isn’t much of a lady.” The group nods, grumbles. Alec watches their faces, puzzled by the distinction he doesn’t understand. His aunt drives fast, and there is no doubt that she is a lady. And Melody Keswick, too—she is gentry, but he has heard Roger laud her recklessness on horseback and behind the wheel. Is it the act of competition that changes things? Is it the difference between wanting to go fast and wanting to go faster than someone else? He makes a note to ask June.

* * *

• • •

After lunch the next day Roger takes Alec to a stable near Byfleet. Alec nearly protests missing the afternoon’s races—he wants to be able to tell June about the women and their cars—but the idea of watching Roger with horses pulls at him, too. Roger seems reserved and a little wary, and gradually Alec realizes that there is probably a gambling issue here as well. Perhaps, judging by Roger’s face, a less happy story than whatever is between him and the men at Brooklands.

The stable itself does not provide any answers; Roger is his usual bluff self with the bandy-legged trainer who walks them through the barn, and Alec finds himself as absorbed as ever with the way Roger touches the horses. He wants to know anything as well as Roger knows horses. Cricket is close—how the bat feels in his hands, the way he can almost sense how the air and grass and men will work together with every bowled ball . . . Yes. It’s close.

But that night, after the drive back to Fenbourne, he realizes that what he most wants to understand is June. He wants to know what she is telling him with the cairns, and what each of her smiles means.

He curls into the corner of his bed, watching the moon, wondering if June is watching it, too. Most nights, he tells himself the stories his mother used to tell him—Kipling, sometimes, or tales of Vishnu and Shiva and the Monkey King, but most of all an ever-changing tale of a princess and a bear and their life along a river somewhere. He can’t remember where, and the loss of that detail gives him a pang every time he thinks of it. The maharani and her bear, the river cold as mountain ice. But tonight the details don’t stick, and when he finally sleeps, his dreams are full of the blue sky above the Himalayas, of an avalanche shuddered into life by the sound of motorcycles, of the fire he never saw that consumed his parents and the cholera that had taken them.

* * *

• • •

It’s the next evening that they go to the vicarage for dinner. As they get ready, Aunt Constance fusses over him as if he were much younger, until Roger pulls her away with a laugh. Alec watches Roger, freshly shaved and gleaming in his dress uniform. The men he sees most often are the masters at school, or tradesmen or farmers either in the City or here in Fenbourne. But Roger is the kind of man he can see himself becoming—an officer, like his father, his shoulders broad in the uniform. Perhaps a horse, a commission in the Guides, a return to India.

At the vicarage, June enters the drawing room with her father, exactly as she had the first time he saw her. But she’s elegant now in a way that startles him to the core, in a dress the color of coffee, her hair pulled back. He is not prepared for either the lines of her beneath the fabric or the way he feels when he notices. When she turns to greet Aunt Constance, Alec tries to catch his breath. He is not prepared for June at all.

They fill the room with chatter, Alec and June together by the window with their thimbles of sherry, the adults islanded on the furniture. Alec keeps stumbling over talking about the races, and each time she regards him with her level eyes, waiting, even while he knows she’s listening to Roger and her father talk about what’s happening on the Continent.

Finally she says, “Alec?”

“Yes?” He looks down at her, and realizes for the first time that it’s been a while since they were eye to eye.

“I’m glad you’re here.” She smiles softly at him. His heart larrups.

“I am, too,” he says, feeling the insufficiency. June’s smile broadens as if she feels it too, through him, and forgives it, and she sips at her sherry. Her hair looks so soft, and he’s glad when he hears Mr. Attwell say something about the Ashes and England’s win against Australia last winter. Talking about cricket will be so much easier.

“Australia are looking strong again for the next series,” Mr. Attwell says mildly.

“Alec can fetch ’em back if Australia win,” Roger says, reaching out and poking at Alec’s shoulder.

Alec grins obligingly. Playing for England would be grand indeed. And playing for

the Ashes would take him back through India.

Mr. Attwell acknowledges Roger with a nod. “Say what you like, I prefer my cricket the old-fashioned way.”

Roger grimaces. “Nothing wrong with body-line.”

“I shouldn’t like someone bowling at me like that,” Alec says quietly, and the men both stare at him. Mr. Attwell’s thin mouth curves into a smile.

“In any event,” Aunt Constance says, her words clipped, “isn’t what’s happening in Germany more important?”

“We beat them once,” Roger says, shrugging and lighting a cigarette. “If need be, we’ll do it again.”

“But the cost,” Aunt Constance says. “Another generation, lost.”

Alec turns and meets June’s eyes. It feels good to be included as an adult, more or less, but it was easier when they could slip off to the conservatory together, away from the politics. He takes a step closer to her, wishing, although he’s not quite sure for what.

She smiles again, as if she knows his thoughts, but then she moves nearer to where Roger is talking about the last war. Alec follows.

“If there is another war with Germany, mightn’t it mean the end of empire?” she says, and the adults stop talking and turn. Alec realizes abruptly that they are listening as if she is one of them. Of course they are.

She continues. “Whether we win or lose—”

Mr. Attwell says, “We’ll win handily enough, if it comes to it.”

“That great wally at Downing Street will give the Huns his own bloody children if we let him,” Roger mutters. Mrs. Attwell frowns and murmurs something about language, and Roger goes red.

“In India they’ve begun to partition the electorate,” June says. “I should think that another war in which we expect the Indians to fight for Britain might make that fragmentation more pronounced.”

“The end of the Raj,” Aunt Constance says.

Alec doesn’t know what to say—India has been part of his family forever. He is the third generation of Oswin to be born there, the fourth to feel the shattering rains of the monsoons. Intellectually he understands, almost, but in his heart, it’s a bewilderment.

“Speaking of India,” June says, eyeing him, “or, not India, quite, they’ve nearly made Everest this time.”

“They might manage next time,” Alec says.

“Lady Houston should be credited more,” Aunt Constance says. “I expect she would have liked to see them succeed. It’s quite an investment.”

“It’s a faith,” Mrs. Attwell says tersely. “Imagine such a life.” Alec nods. He had followed the trip closely in The Guardian, the pictures ranging through his memory. Impossible photographs of impossible acts, biplanes soaring above the clouds, the sharp prow of the mountains in the background. He can’t look at the pictures without thinking about the crystallized kernel of absence his parents’ deaths left in his life, but also he can’t help thinking about what it must be like to fly. To be human, but other, thousands of feet above the surface of the earth, freed from all of it.

“On top of a mountain is not a good place for a woman,” Roger says. He narrows his eyes at his sister, who looks like she wants to interject. “Don’t look at me like that, Connie. Basic matter of strength, that’s all. Women aren’t suited to adventure.”

June frowns, clearly vexed. “What about Gertrude Bell? Or Amelia Earhart?”

Roger smiles indulgently at June. “Exception proves the rule.”

“We have our roles for a reason,” Mr. Attwell says. June looks away, her lips pressed into a thin line.

Alec smiles at her. “There were women racers at Brooklands. Mechanics, too.”

“When the next war comes,” June says, glancing at Alec’s aunt as if seeking her approval, “I suppose we’ll see what women are capable of, if all the men go to the front and we’re needed again for factories and farms.”

“That’s enough, June,” Mr. Attwell says mildly, and June blushes, looking down at her hands.

Mary comes in to announce dinner, and as they all rise to their feet, it feels as though the room has let out its breath. As they sit, June leans close and whispers to Alec, “Every time I see a picture of Everest, Alec? I think of you.”

* * *

• • •

Two mornings later, when a cairn made of sharply angled shears of slate appears beneath the willow in front of the cottage, he thinks of Everest, and something shifts in his chest, as joyous as an otter. Perhaps he doesn’t have to ask her what it means after all.

1934, Fenbourne

In flood years, the River Lark and the various rills and streams and minor tributaries that feed from it creep into the roads and lanes of Fenbourne. June has lost count of how often the bells of St. Anne’s have rung the alarm when the river has crested too high, and twice that she can remember the water has edged up nearly to the steps of the church. Everyone knows the council needs to fix the sluices and clear the canals, or the flooding will just get worse, but so far they are mired in inaction like the tangles of branches and scummy dross that catch in the gates of the lock.

June wakes one morning the summer she turns fifteen to find the half-familiar stench of muck filling the air. She lies still, breathing it in. Not a flood yet, or the alarm would have rung, but something. And the floods are a winter problem, for the most part, when the rain fills the ditches and the wind brings more water in from the Wash. She stands and goes to the window. There’s a ginger tom lying in the lane that runs alongside the vicarage, basking in the bright yellow morning and washing his paws. But no mud. Maybe she’s dreamed it?

Today is the day Alec comes home. He’s been away at school in London, and his absence has cut her to the bone. It’s unfair, of course; she’s been at school too, far to the west in Winchester, and no matter how often they write each other, the letters are no real substitute for what they have when they’re together. They can’t meander along the riverbank or explore the lanes, and she can’t watch his dark eyes spark with interest when she shows him one of her maps or talks about someone they both know in the village. But she’s also been back in Fenbourne longer, and it feels like an entirely different place with Alec not in it. She’s surprised by how unsettling it is to move through a day here without seeing him, or without feeling the curious weight of his seeing her. The year before had been harder; there was the adjustment to being away from home completely, not just the shift of being apart from one’s shadow.

June settles herself into the window seat, watching the cat. He has stretched himself out like a bow, a proud arc of fur and sinew. A breeze pushes over him, ruffling a tangle of wild roses that tumbles into the lane. The cat stands, stretches fore and aft, and meanders away, his tail waving behind him like a periscope. June looks out over what she can see of the village, but most of it is behind her—her window faces north toward the river. Toward Alec.

* * *

• • •

On the north bank of the river lives a boy who carries with him a stub of pencil and a battered notebook. Inside it, he draws pictures of the stars and moon, of boats he remembers from what seems like a lifetime ago, of the lines he sees in the bark of the larches and oaks that stand outside his aunt’s house. On the south bank, waiting, June makes maps of the world around her and lays them out across the ancient, creaking atlas in the study where her father composes his sermons. He is a dry man, and his sermons read accordingly, but his study is full of the deep smell of leather and books, and the small thunder of letting a map roll itself back up. She opens a notebook and lists the railway timetables from Ely to Norwich and King’s Lynn and London by memory.

Her father teases her sometimes about her need for information, the hunger she has to know everything. She can’t explain it, any more than she can explain the way maps unfold in her head, or the stories she sees in equations. Alec never asks her why she needs to know—he quietly tries to find the answe

r. She maps the cities for which she’s listed the times. Compared to hers, Alec’s drawings are like puzzles, lines that leap and curl, stars that don’t exist, imprecise but somehow perfect even when she doesn’t understand them. She looks down at the paper on which she has been making her own lines, satisfyingly straight. She smiles.

The maps keep her attention, as they always do, until Mary Hubbox bursts in an hour or so later.

“Begging your pardon, Miss,” Mary says, “but Master Alec is here for you.”

June looks up, a little lost. She’s been deep in re-creating a particular street in Winchester, not far from school, where she and her friends go to buy ices on the rare afternoons that they can leave the grounds of St. Swithun’s. The vicarage seems almost imaginary. As does Alec, and then he pokes in his head behind Mary.

“Thank you, Mary,” June says. Mary bobs a light curtsy and leaves.

Alec has grown again. His jaw is thicker, and his hair, which he has always let fall how it will, is now carefully combed back over his head and neatly parted. He is not quite a man, but not the boy he was last summer, either. Over the Christmas holidays June had noticed that he was changing, but this seems abrupt. She can’t decide how she feels about this new version of Alec.

“I say,” he says, and June’s eyes widen at the new depth of his voice, “can’t just leave a fellow standing around. Got scooped up by the pater.”

“Hello, Alec,” she says, wondering what her father had to say to him. “Welcome back.”

He strides forward as if he’s going to hug her, then stops himself. June has a bristle of feeling—not panic, exactly, but a new kind of confusion. An embrace from a young man, even this young man, perhaps especially this one, is another thing entirely now. She can almost see him look through the floor as if seeking out her father. Ah—perhaps he has given Alec some kind of hint about keeping to himself. But Alec is suddenly bigger, more assured, more like his own person than she’s ever seen him. For an instant, she hopes her father’s speech, if there was one, doesn’t stick.

The Stars We Share

The Stars We Share